How Covid-19 related losses may impact banks’ transfer pricing policies

How Covid-19 related losses may impact policies

It is anticipated that the current ongoing crisis will impact lending activity and may trigger losses within banks for FY20. More generally, the pandemic is unprecedented, and previous transfer pricing situations and methods may not be applicable to the 2020 situation.

The OECD, which provides the general transfer pricing guidelines, did not cover crisis situations such as the one at present. As a matter of fact, the only crisis actually covered by the OECD is consequences arising from earthquakes!

Therefore, under the current circumstances, how could Covid-19 related losses or reduced profitability impact banks’ transfer pricing policies for FY20?

Allocation of profits within a credit institution

According to OECD guidelines, when setting up an internal transfer pricing policy it is necessary to elaborate the value chain of the global credit institution. This value chain is essential to highlight which entities or business units perform the most creation of value and where “substance” is located, in order to define where profits should be taxed. The outcome of this value chain may differ substantially from an accounting or even a contractual perspective.

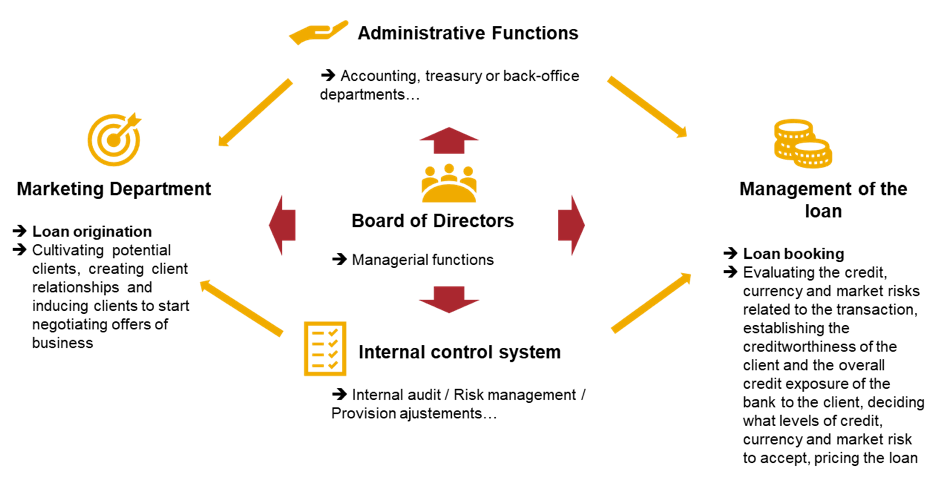

For instance, in the process of granting and managing a loan within a bank, from an accounting or financial angle, the most relevant functions in a value chain could be expected to be the board of directors or the internal audit function. The functions involved in the management of a loan could be illustrated as follows:

Under an OECD perspective, the relevant approach consists in analysing the institution’s actual functions and their relative importance according to facts and circumstances in light of the “Key Entrepreneurial Risk Taking” (or “KERT”) activities. More specifically, the banking industry’s internal transfer pricing policies should be established with even greater attention due to its essential role in financing a state’s economy, and the overlaying regulatory framework.

When performing a functional and factual analysis, it is common to begin by separating the routine (or “support”) and non-routine activities.

Furthermore, subsidiaries or business units performing routine functions are usually defined as “limited risk subsidiaries”. In practice, routine functions within a credit institution are associated with support and back-office activities - including to a degree, the general management - often centralised in the head office. The global banks which include such activities generally use the transactional net margin method (TNMM) to define the appropriate compensation of their limited risk subsidiaries. This method involves comparing the net profit margin of these subsidiaries with the net profit margin of comparable companies by using an appropriate profit level indicator (“PLI”). The most commonly used PLI for such service providers and support functions is the Net Cost Plus (“NCP”). As a consequence, the profit allocation to routine functions is usually low, but recurrent and guaranteed.

By contrast, a larger portion of profit is usually allocated to non-routine activities, which includes more entrepreneurial and risk-taking activities. Traditionally, regarding credit institutions, the most critical risks considered for tax purposes are credit risk[1], market interest rate risk[2] and market foreign exchange risk. In sum, regarding the attribution of a loan, the KERT functions within a lending institution are commonly the ones associated with the origination and subsequent management of a loan.

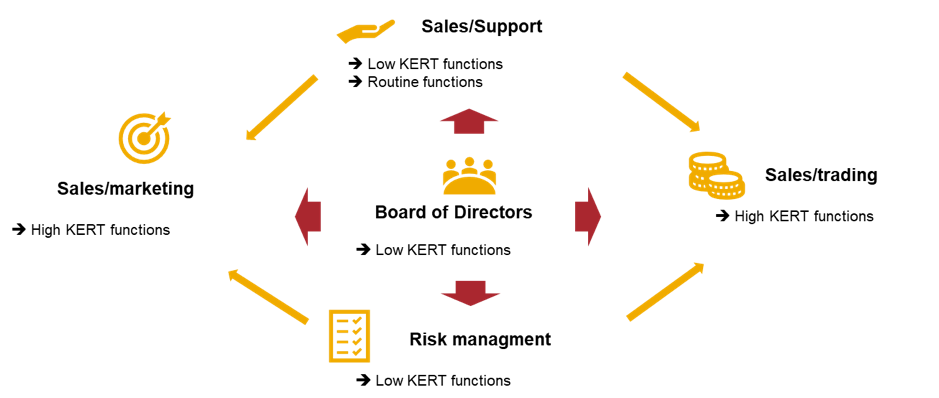

As an example, and referring to the illustration above, in the process of granting and managing a loan within a bank, from a transfer pricing perspective the most relevant functions in a value chain could be expected to be the sales and marketing teams as well as the risk management ones. This could be illustrated as follows.

Credit institutions will likely have to review and modify their transfer pricing policies because of the economic crisis. Thus, a lot of them have structured their transfer pricing policy around an entrepreneur and limited-risk entities. The latter have a guaranteed profit, while the entrepreneur gets the residual profit or loss. In this context,

However, FY20 is unprecedented and these principles may not all be applicable to FY20 transfer pricing policies.

Allocation of profits or loss within the value chain of global financial institutions in 2020

As mentioned, FY20 is unprecedented. The lockdown was state-driven. Banks have even been acting as agents for governments (i.e. taxpayers) and central banks (currency holders) through the distribution of emergency loans and to this extent, credit risk has been transferred from lending institutions to states.

Each country is protective of its banking system and therefore, tax administrations are likely to not accept that global financial institutions guarantee the same profit in 2020 to their limited risk functions (1) and will check that in the case where a loss would be incurred by certain global financial institutions, the said-loss is properly allocated along the high-value contributors in the value chain (2).

1. Tax authorities will likely not accept that global financial institutions guarantee the same secured profit to their limited risk functions in 2020

As a result of COVID 19, credit institutions will certainly have to reconsider and modify their transfer pricing policies.

Many of them have structured their transfer pricing policies around entrepreneurial and low risk entities. The profit of the latter is guaranteed, while the entrepreneur receives the residual profit or loss. In this context, limited risk service providers have so far been remunerated on a cost-plus basis.

a) Should the cost basis of the limited risk service providers be impacted by the COVID-19 crisis?

Some of the low risk service providers may not have provided their services during the confinement period, at least. In this situation, there is no reason for them to charge their costs plus a mark-up as if they had provided their services.

Moreover, some of these service providers may have received financial assistance from the state where they are located, including indemnities for partial unemployment. In this occurrence, the financial assistance received from the states where global financial institutions are located, should reduce the cost basis used to price the intragroup services of the low risk service providers.

Global financial institutions whose 2020 financial aggregates will be strongly affected by the Covid-19 crisis, both in terms of turnover and results, could be required to restructure their value chain and relocate or restructure some activities resulting in a reduction of activity or even the closure of certain branches or locations abroad. These restructurings will affect the transfer pricing policies of global financial institutions. As a result, the global financial institutions will have to organise the allocation of restructuring costs between their branches or subsidiaries. In this context, it will be important to attribute restructuring and closure costs in accordance with the arm's length principle. In particular, compensation related to the rupture or renegotiation of intra-bank contracts will have to be carefully examined, taking into account the existence of possible compensation clauses in existing contracts. This allocation of restructuring costs will have to be duly documented in order to be prepared for future transfer pricing audits.

b) Should the comparable studies used by the low risk service providers of global financial institutions be adjusted in 2020?

Regardless of the method used to determine an arm's length price, its confirmation requires a comparison with a transaction or result realised by an independent company (the comparables). This confirmation of transfer prices by reference to independent comparables will have to consider the effects of the economic Covid-19 crisis.

In order to validate that a current or a future transfer price is set in accordance with the arm's length principle, a search and selection of comparable companies whose financial data is most often available on databases with a time lag of one year is generally carried out.

In an economic crisis context, companies are therefore facing the difficulty of having to validate the level of their transfer prices by reference to comparable data that does not consider the impact of the crisis.

As a result, comparability studies carried out in 2020 may not reflect current economic conditions and thus prevent the setting of a fair arm's length price for future transactions.

The fact that tested parties and comparable companies can react differently during the Covid-19 crisis, particularly in terms of demand and sales, could also compromise the reliability of transfer pricing methods.

As a consequence, benchmarking strategies may need to be revised by targeting subsets of comparables that are closer to the tested party (both in terms of sensitivity to an economic downturn, as well as general characteristics and timing). These subsets can be arrived at by refining existing comparable companies’ sets, by eliminating companies that did not face similar adverse economic conditions or that do not have sufficient financial data.

Global financial institutions should also consider broadening search criteria to include companies with similar sales declines by removing certain screening criteria that would allow for the identification of comparables experiencing financial distress (i.e., bankruptcy or operating losses). Moreover, global financial institutions should apply certain screens to ensure that highly profitable comparables that are not impacted by the economic crisis are not included in the comparables sets.

In addition, the use of a multiple-year approach might not be suitable any more for generating reliable comparables in all cases. Global financial institutions may evaluate whether the use of a year-by-year approach could better capture the effect of events causing dramatic changes in the market in a given year. There are instances, however, where the use of multiple-year averages or pooled financial results for years in which comparables suffered from similar economic conditions (whether or not sequential/concurrent) could help to develop a more reliable range.

Again, global financial institutions will have to adjust their benchmarking approaches in 2020 and will have to be able to justify these changes when they are subject to a tax audit for year 2020.

That is why before taking action, global financial institutions should consider performing financial simulations using their best forecasts of 2020 and consult with transfer pricing experts in order to figure out the required adjustments.

2. Global financial institutions which will be in a loss situation in 2020 should check their loss is properly allocated along the high value contributors of the value chain

Under normal conditions, it is the entrepreneur of the global financial institution who defines the strategy, which is executed by the limited risk subsidiaries under its control and monitoring. If strategy of the entrepreneur generates profits, the entrepreneur gets the residual profit. Conversely, if the strategy defined by the entrepreneur generates losses, the entrepreneur gets the residual loss or reduced profitability.

In the current Covid-19 context, it is not the strategy of the entrepreneur which will generate the overall loss of certain global financial institutions in 2020. It is the shutdown of certain sectors of the economy, managed by all the states around the globe, which originates the 2020 losses of certain global financial institutions.

Due to the above origin of the losses, it is to be anticipated that the tax authorities auditing the 2020 taxable result of the entrepreneurs of these global financial institutions may challenge the fact that they receive the entire residual loss.

For all the reasons above, global financial institutions which will be in a loss situation in 2020ought to assess the possibility of sharing their overall 2020 loss with at least the most complex 2020 contributions in the value chain which cannot be easily benchmarked.

Before making such a decision, the global financial institutions ought to perform financial simulations and consult with transfer pricing experts in order to take decisions in all good conscience.

[1] Credit risk: the risk that the client will be unable to pay the interest or to repay the principal of the loan in accordance with its terms and conditions.

[2] Market interest rate risk: the risk that market interest rates will move from the rates used when entering into the loan agreement. Market interest rate risk can arise in a variety of different ways depending on the nature of the interest rate on the lending and on the borrowing. For example, the borrowing could be fixed but the lending floating or even if both the lending and borrowing are floating there could be a mismatch in timing. Interest rate risk can also arise due to the behavioral effects of market movements on the bank‘s clients. For example, a decline in interest rates may encourage clients to prepay fixed-rate loans.